While reading a text on the refraction of light, I came across the disturbing formulation “light chooses the fastest path”. Should I take this to mean that photons know the future, they know where they are supposed to go, they know what the properties of the environment they will travel through will be, and they choose their path accordingly?

Photons are particles with zero rest mass moving in a vacuum at the speed of light. As bosons, they are not constrained by the Pauli Exclusion Principle and can pass through each other or occupy the same quantum state. In addition, they exhibit particle-wave dualism, which means that sometimes the motion of a particle fits the description of their behaviour and at other times they behave more like a wave. Therefore, the term quantum of electromagnetic waves is also appropriate for them.

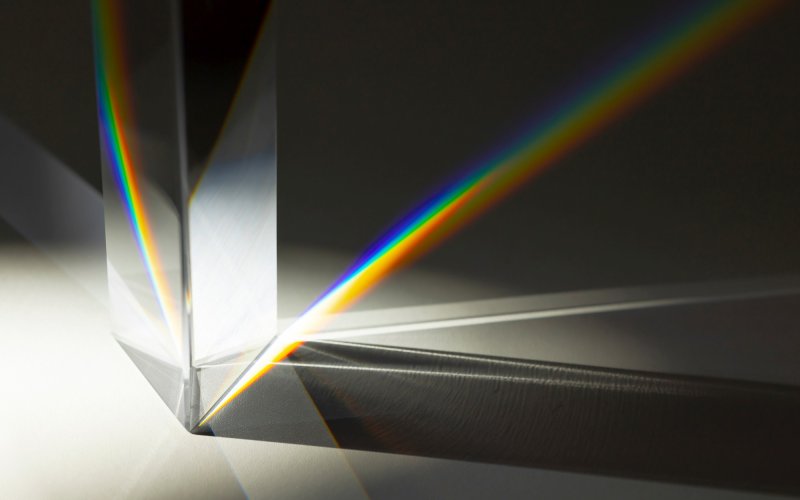

Photons move in a straight line in a homogeneous environment, but if they encounter an environment with different properties, their trajectory may change. When they hit a mirror, they bounce off it according to the principle that the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection. This principle is relatively easy to figure out and was therefore known since ancient times.

Representation of the light ray refraction by wavefronts. In a blue environment, the wave propagates more slowly and therefore the ray as a whole bends.

However, light may encounter an environment in which it can propagate, but this environment has different optical properties than the environment from which the light came. Typically, the ray passes from air into water or glass. In this case, a mysterious thing happens to it. The path of the ray breaks at the point of transition to another medium and the ray continues on at a different angle. This refraction is described by Snell’s law, which says the ratio of the sine of the angle of incidence to the sine of the angle of refraction is a constant quantity for a given pair of media, determined by the ratio of the speeds of light in the two media. This is because light moves more slowly in non-vacuum environments, and the speed of light movement is different for each environment.

So we know at what angle the light beam will bend, but why does it do that? One explanation is offered by Fermat’s principle, formulated as early as 1662. It says that light always travels between two points along the fastest possible path. It will move more slowly in one environment, so it will try to spend as little time as possible in that environment, but at the same time so that it doesn’t take a disproportionately long path in the faster environment.

The analogy of a lifeguard rescuing a drowning man is often used. Imagine the situation of a lifeguard standing on the beach and seeing a man drowning in the sea away from him. The lifeguard could run and then swim right up to him, but because he swims slower than he runs, he would spend too much time swimming. He could also run along the beach as close to the man as possible and then swim for a short distance, but then he would take too long to run. The ideal is to find the path that will get him to the drowning person the fastest.

A diagram of the possible pathways along which light can propagate from one medium (e.g. air) to another (e.g. water). However, only on one of these paths does light travel the distance between the two points the fastest.

Light behaves in the same way when it has to get from point A to point B located in a different environment. It looks like it has determined where it wants to go, surveyed the situation, figured out the speed of its movement in the other environment, and planned the fastest route accordingly. This can look a little spooky, as if the light is a clairvoyant knowing the entire past and future of the world. But it’s not that worrying even though some interpretations of Fermat’s principle do use terms like “light chooses the fastest path”.

Quantum physics will solve the problem with a path integral. It will consider all possible paths, but during the calculation the alternative paths will be discarded and only the one in which the time of motion reaches a minimum will remain, i.e. the fastest path along which the light finally travels.

But the motion of the beam can also be explained by the wave behaviour of photons, and fortunately this no longer requires any prediction of the future and consideration of all possible paths. The motion of a photon can be interpreted as the motion of successive wavefronts. We can imagine, for example, waves heading towards the coast one after the other. If the waves arrive at the beach at an angle, one edge of the wave is already on the sand, where its motion slows down, while the other still has the sea beneath it. Because the wave cannot break, it gradually turns. In the same way, a light wave will turn when it hits another, slowing environment. It doesn't even need to know the future of the universe to do that.

Want to ask something?

Send us an e-mail with the subject “Physics mysteries” to the address:

We can't wait to tackle your interesting questions!